Sulo Commencement Exercises - Mr. Dalisay's Keynote Speech

Chancellor Carmencita Padilla, Dean Charlotte Chiong, Members of the Graduating Class of 2018 and their proud parents, fellow members of the faculty and staff, friends, ladies and gentlemen:

Thank you all for this great honor of being invited as your commencement speaker. I’m still not sure exactly why a Professor of English is speaking to a corps of medical graduates and professionals, and I know that many of you will be wondering as well what I have to say. But I will do my best to make it worth your time—and mine—for at least one good reason.

This will probably be the last time I will be wearing this sablay as a UP official, as I will be retiring six months hence after 35 years of service to the University. So this, too, is my commencement as much as yours—the start of another phase of life. This, too, is my valedictory, my final opportunity to share with you some insights gleaned from my life in UP as student, teacher, and administrator.

And, may I add, as a writer of fiction, which beneath all these robes and titles is what I really am—a storyteller.

Thirty-six years ago, as a young and aspiring writer, I wrote a story about a doctor. The story was set in the Philippine Revolutionary War, and it dealt with an old, cynical doctor named Ferrariz who had made a mess of his life and, seeing few other options, had signed up to become a doctor with the Spanish army, fighting the Filipino insurgents up in the mountains. His unit is taking heavy losses, but one day they capture a rebel—a fifteen-year-old boy named Makaraig, who is badly wounded. Ferrariz’s superior, a major, orders Ferrariz to save the boy’s life.

Let me quote briefly from the story:

… For three days he worked like a driven man, cleaning out and dressing the boy’s wounds, setting the arm, packing cold compresses upon the swellings. He felt godlike in that mission. He unpacked his books from their mildewed boxes, brushed off the fungi and reviewed and relived the passion of the way of healing. He watched miracles work themselves upon the boy and stood back amazed at his own handiwork. When he was through, when he faced nothing more than that penance of waiting for the boy to revive, Ferrariz realized that his eyes were wet. Not since he stepped into the University, knowing nothing, had he felt as much of an honest man.

In other words, this doctor, who had lost faith in his talents and in his hands, suddenly finds himself revived and redeemed by his mission of curing a battered boy. By saving Makaraig, he saves himself.

But the story doesn’t end there. The major has his own reasons for bringing a rebel back to life—to torture and interrogate him, and eventually to kill him, and that’s where the story closes, in a long scream that pierces the doctor’s newly awakened soul.

That story, titled “Heartland,” went on to win in the 1982 Palanca Awards for Literature—my very first First Prize. But why did I write a story about a doctor who saves a patient, only to have him murdered by others? Why did I write a story about self-redemption?

The story behind the story was that while I was only 28—and I’ll have something to say about being in one’s 20s later—I felt like Ferrariz, an old man who had gone adrift and who was just going from job to job with mechanical indifference. It was martial law, and despite the fact that I became a political prisoner at 18 and spent seven months in a camp in what we now call Bonifacio Global City, I had been working as a government propagandist for the past eight years, churning out press releases, speeches for President Marcos, and glowing articles about his New Society.

I needed to remind myself that I could write good fiction (what I was writing for work was bad fiction), that somewhere in me was truth waiting to be said.

But beyond my personal story, I have always been fascinated by doctors—as subjects of stories, and as writers themselves.

Almost thirty years ago, as a graduate student in Wisconsin, and again for some strange reason, I was invited by the Philippine Medical Association of Michigan to speak at their annual dinner in Detroit. I later wrote an essay about that memorable experience, because the doctor who met me—a very accomplished man—did so in a gleaming black-and-white Rolls-Royce, and I had to check my shoes before stepping in.

I don’t know how many doctors actually listened to me above the chatter and the clink of glasses, but I gave a talk about “Writing as Healing: Doctors, Writers, and Doctor-Writers,” in which I noted how many well-known writers were actually doctors by training: the French Renaissance satirist François Rabelais, the Russian playwright and short story master Anton Chekhov, the American essayist and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes (father of his namesake, the equally famous Supreme Court Justice), the American poet William Carlos Williams, and the British writer W. Somerset Maugham. In our own literary history, of course, we have Jose Rizal, and the short story writer Arturo Rotor. In modern times, we have William Nolen, Michael Crichton of Jurassic Park fame, Oliver Sacks, and my favorite of them all, the brilliant essayist, fictionist, and surgeon, Dr. Richard Selzer.

In his book of essays entitled Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery, Selzer addresses his central interest, the relationship between passion and pathology:

“Someone asked me why a surgeon would write…. Is it vanity that urges him? There is glory enough in the knife. Is it for money? One can make too much money. No. It is to search for some meaning in the art of surgery, which is at once murderous, painful, healing, and full of love….”

This quote demonstrates the strength of Selzer’s writing, which is inspired, graceful, and precise. (“Surgery,” Selzer writes, “is the red flower that blooms among the leaves and thorns that are the rest of medicine.”) At the same time, Selzer also shows what to some of his fellow MD’s might seem a weakness—that is, his refusal to separate philosophy or spirituality if you will from physical medicine. If you think it silly to speak of a colostomy in the same breath that you would speak of love, then Selzer may not be for you.

Beyond Nolen and perhaps even Crichton, Selzer has gone on to write serious fiction about the world of healing—not only about doctors, but about their patients and the lives they lead beyond the hospital. In one of his stories, a woman’s husband dies and his organs are given away to seven different recipients in Texas; she is happy for them, but, of course, is unhappy for herself who now has absolutely nothing left of him. So she tracks down the man who has received her husband’s heart, and much to his surprise, requests him to let her listen to her husband’s heartbeat through his bare chest for one hour. The man and his suspicious wife refuse. She persists, and finally he relents.

It is a bizarre and also funny story—a superb illustration of the humanism we all aspire to, in that it reminds us that the simple needs of human life are still more complex than all the transplantation technologies we can dream of. In dealing with this widow’s grief, Selzer achieves physicianship on more than one level. This perfect synthesis of writer and healer, of sensitivity and technique, was on Selzer’s mind when he answered his own question:

“No, it is not the surgeon who is God’s darling. He is the victim of vanity. It is the poet who heals with his words, stanches the flow of blood, stills the rattling breath, applies poultice to the scalded flesh…. Did you ask me why a surgeon writes? I think it is because I wish to be a doctor.”

Not all doctors can write—although many write prescriptions that can hardly be read. But one doctor who did write, of course, was Jose Rizal, one of my personal heroes whose travels and haunts I have tried to follow around the world from Dapitan, Singapore, and Hong Kong to San Francisco, Madrid, and Barcelona and, two years ago, to his medical studies in Heidelberg. When my creative writing graduate students in their mid-20s sometimes tell me that they have nothing to write about, or are too young and too new to strive for greatness, I remind them of Rizal, who many forget was only 25 when Noli Me Tangere was published. Twenty-five, and already by then approaching the perfect synthesis of the arts and the sciences in the one same person.

Rizal’s example underscores the need to embrace and imbibe art and science as

corporal elements of ideal citizenship. To create a viable national community, we need to promote rational, fact-based thinking and discourse over political hysteria and hyperbole, just as we need to actively recover, strengthen, and sustain the cultural bonds that define us as a people.

Speaking of political hysteria, one of my hobbies is collecting antiquarian books, and one of my recent acquisitions was a bound volume from 1822 of a Boston-based magazine called The Atheneum, which collected articles from other magazines from around the world. I was attracted to this book because it carried a report titled “A Massacre in Manilla,” about of a brutal massacre of foreigners—English French, Danish, Spanish, and Chinese, among others—that took place in Manila in 1820. Scores if not hundreds of people were killed by a rampaging mob, following a false report that they were responsible for fomenting a cholera epidemic that had decimated the natives by giving out poisoned medicine. Does this sound familiar—alleged mass murder by vaccine?

So history keeps repeating itself, partly because, despite all the wars and dictatorships we have suffered through, we never seem to learn, although some of us try to teach.

For the past 110 years, that has been part of the mission of the University of the Philippines, our national university, the bearer and champion of our people’s hopes. Or at least, that’s the noble intention. Through our general education program, we try to produce graduates who can be as conversant about Greek tragedy as about the Law of the Sea and thermodynamics. The premise is that a well-rounded, well-educated student will elevate not only himself or herself but also his or her community and society, bringing people together in common cause.

Again, that’s the ideal case. We know that, in practice, while UP has produced scores of such exemplars as Wenceslao Vinzons, Fe del Mundo, Jovito Salonga, Manuel and Lydia Arguilla, and Juan Flavier, and while we graduated 29 summa cum laudes from Diliman this year, we also know that many UP students and alumni have flunked, and flunked badly, especially in the moral department. In other words—and it saddens me as a UP professor to say this—intelligence never guaranteed moral discernment or rectitude, and as proud as we may be of our nationalist traditions and contributions to national leadership, much remains to be done to ensure that we imbue our students not only with skills but with principles. In other words, just as we ask physicians to heal themselves, we educators first have to teach ourselves.

This is why I began this talk with my story about Dr. Ferrariz and his seemingly futile gesture. What that story really wants to ask is: What is life without freedom? What is knowledge without values?

What does a cum laude mean or matter if it will not be used to relieve human suffering but only to enrich oneself and one’s family? Of what use is a glittering GWA of 1.25 if your moral GWA is a murky 3.0? How can you study to save lives and yet remain silent in the face of its wanton loss—not even by disease or accident, but by willful human policy?

There is, indeed, no more life-affirming mission or profession than yours, and in a season of slaughter, to affirm life can be a radical and even dangerous proposition.

It needs to be pointed out that, contrary to popular misimpression, UP has never been monolithically radical. For every activist who walked out of class to join a protest rally, at least five remained behind, intent on simply finishing his or her studies, no matter what. Those of us in the active opposition were always in the minority—a loud minority, which took more than a decade to generate the critical mass to topple Marcos and martial law.

Indeed, like our country itself, the history of the University of the Philippines has been full of ironies and paradoxes. For example, while some would later see it as a bastion of Marxism or at least nationalism, and certainly of secularism, few remember that UP’s first president was an American and a Protestant pastor named Murray Bartlett—who incidentally championed UP as “A University for Filipinos.”

In reality, therefore, UP like other state universities is still a microcosm of society at large, reflective of its divisions and its differences.

And then again, any self-respecting university cannot be content with the realities on the ground, but has constantly to reach for the unreachable star. It cannot be just a microcosm, but something better than the rest of society—better not necessarily in terms of intellectual superiority bordering on arrogance, but better in terms of the quality of its discourse.

That quality of discourse, informed by scientific reason and artistic empathy, can be education’s best contribution to national community. UP—and our other universities—can and must be the providers and drivers of the truth, and of the careful and insightful analysis that can ventilate issues of national significance—like Constitutional change, our territorial integrity, the delivery of justice, human rights, and the eradication of mass poverty, hunger, and disease.

The way to help unite a nation is to imbue all sectors of society with an understanding of and a commitment to larger things at stake. And UP is that functional meeting place between the Filipino rich and poor, with our admissions profile now almost evenly divided between upper and lower income students. Beyond dealing with the larger national issues as teachers, researchers, and experts, we in education must ourselves be avatars of reason, compassion, and tolerance, while remaining steadfast in our defense of academic freedom as the requisite of knowledge generation. In our classrooms and conference halls, we must create and provide the forums that will ventilate these issues in ways that social media cannot. And we have to learn how to listen again, to see why people of different opinions believe what they do.

As President Concepcion said in his investiture speech last year, we in UP should focus “on finding, in this University, our common ground, a clearing—a safe, free, and congenial space within which its constituents can teach, study, and work productively to their full potential.

“UP must be that special place within which it should still be possible—despite all divisions and distractions—to work together with the University’s and the nation’s strategic interests in mind.

“There should be no better home in this country for the expression of ideas, without fear of violent retribution from one’s colleagues or from the State itself. There should be no more welcoming environment than UP for cutting-edge research, timely policy studies, exciting new exhibits and productions, and provocative art and literature—in other words, the work we have always been meant to do, and do best.”

Let me end with a quote from a favorite source—me—and share something that I have said to every UP graduating class I have been honored to address:

To be a UP student, faculty member, and alumnus is to be burdened but also ennobled by a unique mission—not just the mission of serving the people, which is in itself not unique, and which is also reflected, for example, in the Atenean concept of being a “man for others.” Rather, to my mind, our mission is to lead and to be led by reason—by independent, scientific, and secular reason, rather than by politicians, priests, shamans, bankers, or generals.

You are UP because you can think and speak for yourselves, by your own wits and on your own two feet, and you can do so no matter what the rest of the people in the room may be thinking. You are UP because no one can tell you to shut up, if you have something sensible and vital to say. You are UP because you dread not the poverty of material comforts but the poverty of the mind. And you are UP because you care about something as abstract and sometimes as treacherous as the idea of “nation”, even if it kills you.

Sometimes, long after UP, we forget these things and become just like everybody else; I certainly have. Even so, I suspect that that forgetfulness is laced with guilt—the guilt of knowing that you were, and could yet become, somebody better. And you cannot even argue that you did not know, because today, I just told you so.

May you be the best doctors of and for the people that you can be, and thank you all. Mabuhay ang UP at mabuhay tayong lahat!

By Rory Nakpil (2022)

By Rory Nakpil (2022)

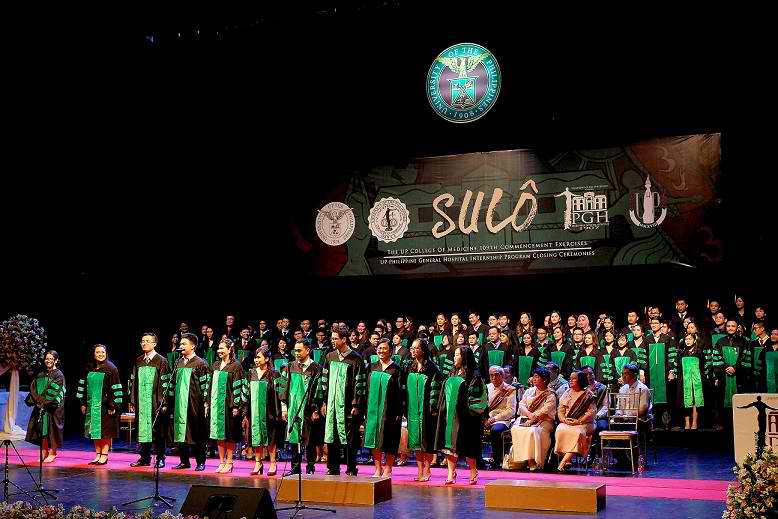

Kumandili: Class 2019 Marches Forth

A grand total of one hundred and forty three students (135 members of Class 2019 and 8 MD-PhDs) marched, and donned their togas, caps, and hoods to be officially named graduates of the University of the Philippines College of Medicine (UPCM). Together with them were their comrades and partners during internship at the Philippine General Hospital (PGH), 181 post-graduate interns (PGIs). Leading the graduation were 8 cum laudes, the second ever batch of the prestigious MD-PhD degree program. Also recognized were the Master’s degree program graduates, albeit briefly as none were in attendance during the program. They named their commencement exercises “Kumandili”, affirming the care they have given as medical students, and the stewards of the health of the nation that they will become as they grow in their careers.

The ceremony began with welcome remarks by Dean of UPCM, Dr. Charlotte M. Chiong, and opening remarks by PGH Director, Dr. Gerardo D. Legaspi. Chancellor of the University of the Philippines Diliman, Dr. Michael L. Tan was the speaker for the commencement address, ingraining in the students the value of “kamusta” -the constant search for answers and knowledge that goes hand in hand with the expression of empathy.

Dr. Kyle Patrick Eugenio, president of class 2019, presented the petition for completion to the administration, and the diplomas were awarded by Dean Chiong. Dr. Rochelle Ann Micah Ventura, president of the PGH post-graduate interns presented the petition for the completion of internship for the PGIs, and their certificates were awarded by Dr. Legaspi. Dr. Josept Mari Poblete, represented the graduating MD-PhD students for their petition of completion, and their diplomas were conferred by Dr. Carmencita David-Padilla, Chancellor of the University of the Philippines Manila.

The march, and the capping and hooding of graduates proceeded, with the graduates kneeling, as their parents and family were the ones to adorn them with their regalias. A heartwarming and inspiring response from Class 2019 was read by Dr. Marianne Adrielle Tiongson with the message to be like Sisyphus, always striving to do better, become better, and grow as professionals and people, for both her classmates, colleagues, and the administration. Dr. Hanna Clementine Tan was named class valedictorian, and Dr. Francis Manuel Resma was named class salutatorian. Dr. Rudolph John de Juras was named the most outstanding intern for Class 2019. The Dr. Alfredo B. Bellisillo academic and leadership excellence award for the most outstanding MD-PhD student was given to Dr. Sheriah Laine M. de Paz. The most outstanding MD-PhD dissertation and also the Oreta-Dizon and Santos Ocampo award for medical research were given to Dr. Josept Mari Poblete. Other MD-PhD graduates were, Dr. Mark Joseph M. Abaca, Academic Distinction in Medicine Awardee, Dr. Charles Patrick Uy, Dr. Pia Regina Zamora, and Dr. Cecile C. Dungog.

Lauds and achievements aside, the graduation was a celebration of the end of the journey of these students, and the beginning of their journey as doctors and the expression and reaffirmation of their desire to serve the Filipino people through their chosen profession. Padayon to our newly minted doctors and MD-PhDs!

View original articleHiraya 2020 WebsiteRewatch livestreamRewatch livestream

Commencement Address by Atty. Jose Manuel "Chel" Diokno

Commencement Address by Atty. Jose Manuel "Chel" Diokno

UP Manila College of Medicine Virtual Graduation Rites, Commencement Address

To the administration, faculty, and staff of the UP College of Medicine;

To the parents, families, friends, and loved ones of the graduates;

And, most of all, to the members of the Graduating Class of 2020:

Congratulations, at mabuhay kayong lahat!

When you entered the UP College of Medicine five years ago, I’m sure this is not how you imagined leaving it on your graduation. But don’t let COVID take anything away from the joy of this occasion. If anything, you graduate at a point in history where it’s become so much clearer how much we need you all and the work you will and already do.

And in any case, you’re not just celebrating this day; you’re celebrating all the hard work you put in, all the challenges you faced, all the things you learned along the way in all your days in your five years in the College of Medicine. You’re celebrating all those who supported you and believed in you. If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes an entire support system of loving, caring people to make a graduate. So don’t let this day pass without showing them your love and gratitude—you may have to practice physical distancing, but don’t let that turn into social or emotional distancing. If you can’t give them a big COVID-safe hug, at least give them a big thank you.

And if it takes a village to raise a child and an entire support system to make a graduate, then remember this: it takes a country to make a UP doctor. That is your badge of honor, and that is your burden too. As graduates of this college, for better or worse, our expectations and hopes for you are higher. We won’t just need you to become excellent healthcare practitioners; we would need you to help pave the way for a better, more equitable, and more inclusive healthcare system. We won’t just look to you to treat and heal our physical ailments; we’ll also look to you to help keep our society alive and well.

We have many great doctors—just as we have many great lawyers, and many great professionals—but we have so few good ones. Good doctors who will serve their fellow Filipinos and do society no harm. Good doctors who will work for a fairer, more equitable, and more just healthcare system for all. Coming as you do from this prestigious College, I know this is the track you are heading toward. But in case you need the reminder—and in the years ahead, you might need it from time to time—then I hope you bear this in mind: competence without compassion will get your nowhere; and competence with compassion will bring you countless joys, satisfaction and success.

So don’t just be great doctors; be good doctors. And don’t just be doctors; be doctors in service of the Filipino people—in service of communities who need your help the most, of families who have the least access to it, of individuals who are often left behind and forgotten.

But aside from looking after the health and well-being of your fellow Filipinos, what else can you do? Well, here’s a piece of advice from my father, Sen. Jose W. Diokno:

Today, we must create within ourselves, as an absolute and essential prerequisite to any change, not only a national consciousness, not only an awareness that we are just elements of a nation whose welfare is more important than our individual interests. But we must also have a national conscience. A conscience that prevents us from doing whatever can hurt the people as a whole even though it may help our business, our families, or ourselves. And a conscience that makes us condemn whoever puts personal interests ahead of the people’s interests.

This, I suppose, is your principle “do no harm” on a larger scale. Or as Albert Camus said in his novel The Plague, which is very timely reading today: “on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences.”

As our doctors, as our healers, as doctors of and for our nation, this is what you are called to do: to be conscious of the nation you belong to, and to be the conscience of the nation you belong to. And that means always keeping in mind the weakest and the poorest and the least of us.

If there’s anything COVID has taught us, it’s that we’re only as healthy as the weakest of us. And the same goes for most things in society: our country is only as rich as the poorest of us, only as strong as the most vulnerable of us. And for better or worse, in very much the same way, your work as doctors of and for the nation will be judged not by looking at the state of the healthiest, strongest Filipinos, but by the weakest, most vulnerable ones. You will be judged not where our healthcare system is at its most robust, but where it breaks down the worst.

This might sound difficult, if not outright unfair. I also mentioned higher expectations and higher hopes earlier. But that is what you signed up for when you entered the UP College of Medicine, and why you survived and thrived in it. You’re here because you know deep in your heart, whether or not you thought of it consciously or even had the words for it, that honor comes before excellence; that compassion and competence should be two sides of the same coin; that service is so much more important, and worthwhile, and fulfilling, than personal success.

And we expect so much from you only because we know how much you are capable of. Whenever you feel the way ahead is unbearable, just remember what you had to hurdle to get where you are—all the demanding classes, the difficult examinations, the impossible schedules, the bone-deep exhaustion, the painful life lessons, and possibly even broken hearts along the way. But you all made it here. And I’m very excited to see where else you will go from here.

And so here’s my wish for you, Graduating Class of 2020: may you be good.

Be kind. Be brave. Be generous. Be fair. Be honest. After five years of all the specialized knowledge you’ve learned in med school, this might seem laughably simple. But goodness often starts from the most basic, most simple things. One hundred fifty-eight good doctors like you are worth more than a thousand great doctors without compassion and without hearts for service. One hundred fifty-eight good doctors like you could be enough to serve as the clearest, strongest voice of conscience this country has ever had—especially in trying times like ours. One hundred fifty-eight food doctors like you have the power to change this country, if not this world, for the better—as I am sure you will, someday very, very soon.

Congratulations, UP Medicine Class of 2020!

Message from the Class of 2020 by Dr. Uriel C. Cachero

Message from the Class of 2020 by Dr. Uriel C. Cachero

To Practice Medicine is to Serve Justice

We've learned many things in our long journey through medical school. We’ve gained the skills required to understand the ills of our patients and piece together solutions in tandem with our residents, fellows, and consultants. We learned to listen to the stories of our patients and their bantay's. In these stories, we understood the socioeconomic factors that led to the situations that we meet them in. I'm sure all of us mastered the skill of pushing stretchers and oxygen tanks at the same time. Keep quiet though, you know we're not allowed to do that. But that’s okay, after all, it’s for the CT scan schedules we fought so hard to get approved. We know that it wasn’t the manong's fault that we needed to do it ourselves. After all, they were just as tired as we were.

"Pagod na 'ko."

We all know what this feels like; what these words truly mean -- that tiredness brought out the monsters in some of us. There were times when we've snapped at a patient or a bantay, even though the situation that they're in was not their fault. There were days when we’ve been walking around the hospital nonstop, dropping referrals, doing extractions, labeling laboratory requests and vacutainers -- all because we have 16 patients in the ER and we still need to finish all of these before it's our turn to monitor 30 of them. Sometimes, we only remember that we haven't eaten, drank water, or peed all day just when it’s already time to endorse to the next duty team. These were the days when we felt burnt out, empty, and on the verge of tears.

Then, a bantay approached me, smiled, and said, "doc, kain ka muna oh" and handed me a plastic bag with a burger from Wendy’s. Suddenly, the weight on my shoulders disappeared as if I wasn’t carrying anything in the first place. As I sat there, eating as if this meal was the most delicious thing I’ve ever had, I found myself asking:

"Ano nga ba ang ipinaglalaban ko?"

A question, I know most of us have asked ourselves at least once during med school. And during those brief times of reflection, I remember another question we were asked during the first weeks of medical school. It’s something I always go back to during times when I feel like I’ve lost my way.

"What good is it to treat a person’s illness if the person goes back to the conditions that brought about the illness in the first place?"

I don't believe there is only one good answer for it, and to be honest, it frustrates me to no end. But it’s given me a reason to continue on. Because someday, I want to have a future where no medical student will ever have to ask it again.

After all, times are changing on a global scale.

This pandemic made us wish for things to go back to the way they were. But I want to remind you that what was “normal” for us was not much better than how it is now. In truth, it was much worse.

One of the most impressive things about someone trained in PGH was our immense ability to adapt to extremely difficult situations. But that was also one of our toxic traits. We could make neck braces out of cardboard boxes. We used gloves as tourniquets. We used syringe barrels as ampule breakers. But we also used these barrels as tongue guards tied to roughly cut up gauze so that our struggling intubated patient wouldn’t bite their endotracheal tube. These were the same pieces of gauze we used to tie up their arms so they wouldn’t pull the tube that helped them to breathe. They’d end up with fissures on the corners of their mouths where the tube rested and rashes on their wrists as the cloth rubbed their skin repeatedly. I can only imagine the pain they must have felt as air was being forced into into their lungs.

What was “normal” made us forget that things shouldn’t be this way. Our “normal” was one where patients had to leave their homes at 3 in the morning so they could line up at our OPD at 5 only to be seen at 3 PM. Our “normal” was to line up patients in hallways and ask them to find a stretcher, or sit on a wheelchair for 3 days. Our “normal” was to ask our patients if they could buy badly needed glucose strips even though we knew we weren’t supposed to. How could we treat a patient in HHS if we didn’t know their blood sugar? We even asked them to buy more than they needed so we could use the ones left-over for those who couldn’t afford it. The hospital tells us not to do it. These patients should not pay for anything. But when adaptation has reached its limit, what else can we do?

A lot of these patients went to PGH because they had nowhere else to go. Who can blame them if they say, “sorry dok, wala na po talaga kaming pera,” or “pasensya na po, ito lang po ang kaya naming bilhin.” Most of our patients put off going to the hospital because they know how much of a financial burden it is to go here. And even if they do, and they get home safely, how can we ensure that they can afford the medications that we prescribe them? How long until they need to go back because their conditions have worsened again?

We have grown so accustomed to what “is” that we’ve forgotten that this isn’t what medicine is supposed to be. Our reality was a reflection of our patients’ realities. It was a reflection of inadequate resources. And there is not one person or entity to blame. We needed to adapt because it was a patient’s life on the line. We want to give the service that they deserve, but when we have so little, even our all is found lacking.

We cannot allow ourselves to go back to what was. Instead, we must be advocates for true and lasting change. The Filipino people deserve more than just “pasensya na po” and “Ito lang po talaga ang kaya nating gawin”. They deserve more than a tired and overworked healthcare system.

We soon-to-be-doctors will be in a position of privilege. Our culture sees our profession as the wise and noble, for isn't it the most noble of causes to save another's life? Some of us may deny it and think that we have done nothing worthwhile yet, and it's true. It is hubris to think that we are better than other professions. We are mere hatchlings, barely able to flap our wings. But most Filipinos do not know that. The addition of two letters at the end of our names demand to be placed on a pedestal. And that's okay. That means that we are in a position to influence change. But to influence change, means to acknowledge our own truths.

I know that we're all thankful for what this hospital has given us. I don't think I can ever find the right words to express my gratitude. But to acknowledge that also means that I need to embrace the things that I have lost because of it.

During the second half of clerkship, my grandfather died and I could not be there for him during his funeral. I know my blockmates would have understood if I had left for a while, but I didn’t. I wasn’t pretending that the reason why I stayed was because I wanted to take the noble route (I’m not kind enough to do that), but I knew how difficult it was if even one person from the team wasn’t present. And more selfishly, I hated the idea of having to make-up for twice the amount of time I was gone. That’s also one of the things that this hospital has done to me. But I’ve accepted it. I know my grandfather would have understood.

I no longer regret the decision I made that day, but I do wish that I didn’t need to make that decision in the first place. And I hope that no one will ever have to go through what I have. Because it was difficult. It tore me apart. It was not okay.

And that was the first step. I needed to understand the fact that not everything was alright. Not everything was bright and beautiful and “high-yield”. It’s okay to say that what happened within the hospital left some of us jaded, broken, and maybe even beyond repair. What we went through was more than just difficult. These hardships were enough to last us a lifetime. It could not have been possible if we didn’t have each other. These experiences will be our weapon. While we did not come out unscathed, we are now stronger. We can make things better for those who will come after us. We WILL make things better.

We're almost at the finish line in a race that was never supposed to be a race. And yet before we know it, it's time for us to take our next step forward. We'll bring with us the bits and pieces that we've picked up along the way, and hopefully, we didn't manage to lose anything important.

Don’t lose your way. Remember that health is a right, and that it is the government's obligation to uphold the people's right to quality healthcare. We are worthy of nothing less.

Don’t lose your voice. We must make ourselves heard and lend our voices so that others too may be heard.

Keep your visions sharp, 2020. We have eyes that will not remain shut towards the suffering of others.

Don’t lose your heads. We need them to stay critical.

Don’t lose your hearts. We need them to stay kind.

Hold on tight. We will need our hands to hold on to one another, and our legs to push us forward: to serve justice, to demand health, to fight for freedom. In essence, they are all the same-- for to be a doctor is to join in the people’s struggle.

Our fight is just beginning.

Mabuhay ang mga doktor ng bayan, at para sa bayan! Padayon 2020!

It has been five years since we entered the UP College of Medicine embarking on a journey we had dreamed of for years. Five years later, we may not be together, but we celebrate the triumphs, defeats, failures, and achievements we’ve experienced. It has indeed been a legendary journey — from being the last UPCM batch that got to listen lectures in the BSLR and experience Dr. Bundoc’s paputok pakulo , moving forward as the interns who experienced the lambanog toxicity, Taal Volcano eruption, then now, the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps choosing to cheer on being legendary was preemptive — all because it was just so hard to think of something that rhymed with “twenty”. But at least it leaves us with no choice but to believe that we are, indeed, legendary .

And so for the last time as students of the college, let’s cheer it with pride.

2020, Legendary!